Stories & More

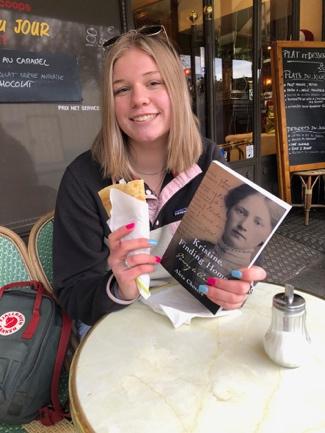

Here on my website you will find some of my writing, and a lot about my grandmother, Kristine Kristiansen Hjelmeland of Kristine, Finding Home: Norway to America. The site is new so come back again for changes and updates.

I have been writing personal essays and family stories for about ten years. With the help of a community of writers, I have learned a lot about the craft and even more about myself. Maybe some of my writing will inspire you to tell a story.

If you are interested in origin stories, immigrant stories and family stories, you will find letters, photos and writing here to interest and inspire you to write your story. If you are family looking for more information, you will find links to my primary source material and genealogy. If you enjoyed Kristine, Finding Home and want to explore themes of heritage, home, ambition, women’s changing roles, more, check out my blog.

I have been writing personal essays and family stories for about ten years. With the help of a community of writers, I have learned a lot about the craft and even more about myself. Maybe some of my writing will inspire you to tell a story.

If you are interested in origin stories, immigrant stories and family stories, you will find letters, photos and writing here to interest and inspire you to write your story. If you are family looking for more information, you will find links to my primary source material and genealogy. If you enjoyed Kristine, Finding Home and want to explore themes of heritage, home, ambition, women’s changing roles, more, check out my blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed